Imagine a Worker.

Imagine workers who knew exactly what the boss needs of them and what they must do to meet that need.

Imagine workers who were self-propelled, self-organising, need no supervision or management.

Imagine workers who the boss sets a task, and they don’t meet again until the task is complete.

Imagine workers who, other than a minimal induction (‘Here’s the toilets. Here’s the boss’s office. We do casual Fridays’) hit the ground running and are productive from the first day.

Those workers exist.

They’re called ‘contractors’ or ‘consultants’.

Is there any reason why the majority of workers don’t work this way?

Other than ‘This is how we’ve always done it’ - and ‘If there are no workers - then what will the boss do?’ - the answer is no.

Own It.

If you have to use someone else’s name or authority to get a point across, there is little merit to the point (you might not believe it yourself). If you believe something to be correct, focus on showing your work to prove it. Authority derives naturally from merit, not the other way around.’ - Kim Scott Malone

Never lend the weight of a superior to an order.

Don’t leave the meeting, boss’s office, or strategic planning day without the confidence you can give directions to the punters as if you came up with them yourself.

If the boss can’t show their working out, then you backward engineer the decision enough to explain it.

Then start looking for a new job.

Wind the Clock.

Though no one uses [the analogue clock in the F16] to keep time, seasoned instructors would say, “Before you make a decision, wind the clock”. It was a seemingly useless process; However, it’s prevented people's first inclination of rushing to solve the problem. Winding the clock occupied the pilot’s attention for just a few seconds, and physically prevented them from touching anything else. It forced their brain to spend time assessing the situation before they acted, allowing them to make far better decisions. ‘ Hazard Lee ‘The Art of Clear Thinking’.

We all need the equivalent of the analogue clock in the digital cockpit of the F16.

We need a habit or routine that distracts us from the decision at hand (Step 1: Step Back) long enough to allow us to avoid - or affirm - our reflexive, instinctive action in response to information.

Mouths of Babes.

‘Instead of arguing over who’s to blame for losing it, let’s assume neither of us is. Then we can both focus on finding it’.

So said my 14 year old to my 11 year old.

The Work in Work Isn’t the Work

Too often the ‘work’ in Work' isn’t the Work.

It’s the politics. The poor communication. The mediocrity. The meaningless meetings. The empty slogans.

The pretending. Everybody pretending.

Acting is hard. Ask any actor.

It’s hard work trying to make sense and coherence out of the mayhem of messages. Day in and day out. It’s dispiriting trying to keep your authentic self breathing as you sink into the quicksand that is workplace nonsense.

Then one day you find yourself on a project with people who are good at what they do. People who are eager to learn from you. People who are generous and honest and straight talking. People who take your work and make it better and therefore you better. They make it all seem effortless. They are not pretending. They are almost oblivious to the nonsense that lies beyond their area of focus. Occasionally they have to down tools and waste time with everybody else in senseless meetings. But then they return to their work and get on with it.

Once you experience those people and that possibility - even if only for an hour or two - you never see work the same way again. Sadly, the majority of workers never experience this. For them, work is work because of the liars and their lying. And the effort of pretending because they think this is what Work is.

A Platypus Doesn’t Quack.

It’s when it’s appropriated to advance an agenda that the skin begins to crawl.

A bunch of people working in the same building becomes a ‘family’.

A random selection of workers becomes a ‘team’ - which naturally means they need a ‘team leader’.

This language cheapens and demeans authentic relationships, whether of kin or emotional connection.

It takes time, trust, contribution, vulnerability, freedom of choice, and generosity to build the kinds of rich bonds that organisations seek to create with a label.

Don’t call a platypus a duck. It’s just wrong.

Besides - 75% of violent crime is committed within families.

Right Twice a Day.

There is one boss more hopeless than the wilfully blind one.

The boss who relies on a subordinate to tell them the time on a broken clock.

Beheading.

If your boss catches you out in a lie -

Or you catch your boss…

What follows is an awkward Dance of the Seven Veils before one of you is beheaded.

Pournell’s Law

In 2006, the coalition forces in Iraq were losing.

The insurgency had forced the coalition to invest too much resources and time into defending the soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen who were in Iraq to seek out, engage with, and destroy the enemy.

Force protection had become its own mission.

In other words, the United States had prioritised using its troops to defend its troops.

You see this in many bureaucracies - particularly in their head offices. Over time, the office grows so much it needs resources just to support its existence. It becomes an organisation within an organisation - with its own hierarchy, policies, and personnel looking inwards to their navels, and insulated from the very organisation it is meant to serve. It snowballs, and is difficult to stop once started. If left too long, there is a generation of workers who only know the head office and how to serve it. If they shift their focus back to the bulk of the organisation, the head office will collapse. This is how they justify themselves.

This phenomenon has been called ‘Pournell’s Iron Law’ after the writer Jerry Pournell who coined it:

In any bureaucracy, the people devoted to the benefit of the bureaucracy itself always get in control and those dedicated to the goals the bureaucracy is supposed to accomplish have less and less influence, and sometimes are eliminated entirely.

Inexperienced bosses address this simplistically by programming token visits ‘outside the wire’. They may also bring in the non-head office workers to participate in decision making committees. But the outsiders are always outnumbered and intimidated and end up simply advocating for their piece of the organisation. They don’t have the strategic perspective nor incentive to do otherwise. Worse is when the outsider representatives end up dictating to the entire organisation, or at the very least fettering decision making as the head office bosses naively give them too much power in a vain attempt to shift mission focus.

Resolution of this problem begins with good leadership. The first job of a leader is to define reality. The leader begins by identifying those functions that need to be grouped in a single ‘head office’ location, and those that can be performed ‘in the organisation’. This can be achieved either by moving roles out to where the work is done, or training the real workers in those functions. For example, instead of having all the compliance people in head office, put them out in the organisation. Not only do they gain a better operational perspective of the value they can add, they are also more visible to the operational decision makers, who are more likely to call on them than when they sat behind desks in the ivory tower.

There will be resistance. If there isn’t - then the workers would have resolved it themselves.

That’s what leadership is: taking people where they otherwise would not have gone.

Hard Deck.

If you’re a pilot, the ground is a disinterested third party.

At least the aviator has an altimeter, an artificial horizon, their eyes, and in modern aircraft, a robotic ‘Terrain! Terrain! Pull-Up! Pull-Up!’ cockpit warning.

What is the decision-maker’s equivalent warning of approaching doom?

Do what pilots do - and create a ‘hard deck’.

The ‘hard deck’ is the height below which pilots don’t fly as it simulates the ground. For example - no dogfighting below 10,000 feet. This allows a large enough ‘fudge factor’ for a pilot to fly above ‘the ground’ - while avoiding the uncompromising response from the ‘real ground’ if the pilot should accidentally break the hard deck.

Have a policy template response of ten working days to any inquiry or complaint - but make it your practice to respond in seven, or even five. The ground is ten - while your hard deck is whatever timing you decide. If an unexpected issue arises that means you can’t respond by five, or seven, then at least you’ve got three days before you come up against your promise to the third party.

Or do the reverse. Instead of declaring a longer time, declare a shorter one. You know a person will take up an hour of your time. Set aside half an hour for them, forcing a hard deck on them to have themselves better prepared. You know you need to get back to that complainant in five days - tell the subordinate you need their response in three - and give them a hard deck.

By setting and sticking to your decision hard deck - you reduce the likelihood of spearing into every decision-maker’s enemy:

Inaction.

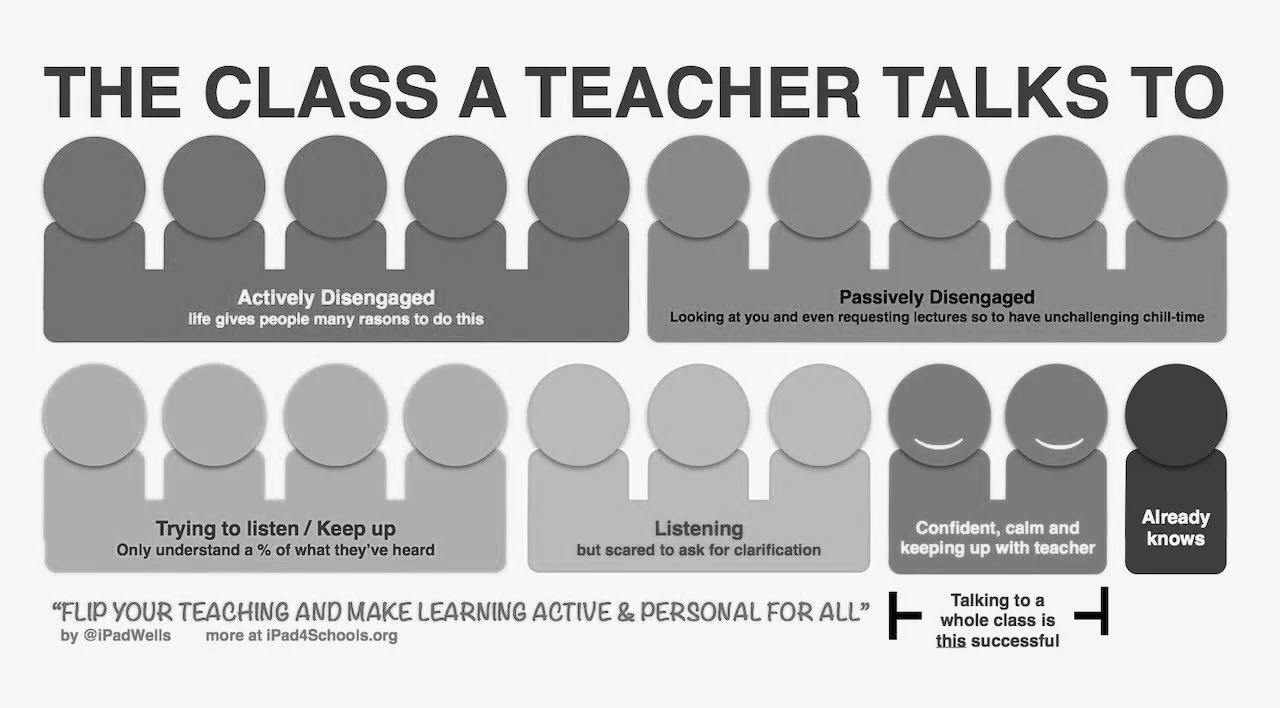

I’ve Never Worked in a School.

I walk past about fifty school students sitting on the grass in the shade beside the river.

A teacher or someone teaching them, sits in front, holding forth.

He’s still talking when I return fifteen minutes later.

The students face him - attentive - their backs to the gleaming river.

Outside. Sunny day. Green grass. Gentle breeze. River. Cityscape. Beach sand.

Who is holding the student’s attention?

The person talking.

A religion teacher developed online learning.

It was an animation of a religion teacher in a classroom teaching religion.

The students sitting in their seats behind desks.

The lesson consisted of the animated teacher asking the animated students questions and an animated student raised their hand and answered and the animated teacher corrected them, in the voice of the real teacher dubbed in.

With literally the world of the past and the present and the future - real and imaginary - available to him to use to teach - the teacher reproduced … the classroom.

The Master’s Tools

The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house.

- Audre Lorde

If the bosses genuinely wanted [insert aspirational slogan here] they would make it so.

If the bosses genuinely wanted to change their organisation - they would have done it.

Unless they were recruited from outside (which poses its own obstacles to change - see below) - the bosses became bosses by exploiting the organisation as it is.

The outfit is the way it is - good or bad - because the bosses want it that way.

The outfit rewarded the bosses by promoting them based on their contribution to the culture the organisation claims to want to change. The outfit recruited the external candidate thought best to make a change or maintain the status quo.

Having built careers that pay for their lifestyles and status on managing an organisation into whatever exceptionalism or malaise now afflict it, the bosses lack the skills and experience and tools to change it, even if they wanted to. So they maintain the status quo they inherited, affirmed them, and learned and profit from.

The new boss from outside will be opposed and undermined by the overlooked and aspirational and often bitter unsuccessful candidates for her job. Their future depends on them protecting the status quo because their ‘corporate knowledge’ is the only advantage they have. If the new boss changes the culture as the new boss intends to, they’ll be left with nothing. Some will switch sides. Others will white ant.

Sure, let’s look innovative and agile by saying we’re innovative and agile.

But at the end of the day - which was the same as yesterday and the day before that - the outfit is exactly the way the bosses want it to be.

A Metaphor for the Tough Days.

Aircraft take flight by powering into the wind.

A metaphor for the tough days.

Devil Spotting.

“What do you think the devil’s going to look like if he’s around? … Nobody is going to be taken in by a guy with a long, red, pointy tail!”

- Aaron (Albert Brooks) in Broadcast News

It’s easy to spot the devil in our workplace.

They’re the ones applauding mediocrity.

Minds Made Up.

I once worked for a company that laid off a third of its staff in a morning. HR told some staff to go into Room 1, and the others to go into Room 2. Room 2 staff were given letters summarily dismissing them.

One woman from Room 2 chased the retreating HR person and pointed out the envelope with her termination letter wrongly described her position. The decision stood - and she still lost her job.

HR routinely operates by stealth. Secretly searching and gathering and reporting.

Summarily executing. While the bosses look away.

‘We can’t risk the punter finding out and getting upset/taking stress leave/upsetting other staff/sabotaging the business,’ they say to justify this behaviour to their bosses. The bosses readily - too much so - agree.

Nonsense. The truth is almost always the twin sins of incompetence and laziness. Best not alert the punter (who was ‘our most important asset’ at our last offsite team building day, remember?) lest they complicate things by giving us a better argument. Or worse - embarrassing us (and our cowardly bosses) by proving we (and our bosses) are wrong.

Minds that are made up don’t care to be confused by facts.

Lure.

Easy things lure us away from better answers.

- Dr. Daniel Dennett, cognitive scientist and philosopher.

The moment you hand someone power, you relieve them of the effort and anxiety and learning and humility and intelligence required to seek the better argument.

It takes an exceptional boss not to routinely lazily deploy that power.

Arguing with The Boss.

When you’re in a company, and especially if you’re a leader, it’s important to farm for dissent because it’s not normal to disagree with your boss … “My job is to please my boss,” as opposed to we want people to feel “My job is to help Powder or Netflix or Pure Software grow. Sometimes, if to help them grow, I’ve got to be willing to argue with my manager,” and that’s okay. And so because it’s difficult, emotionally, in most companies to disagree with your manager, we call it farming for dissent. And we have managers do things like, ‘What are three things you would do differently if you were in my job?’ I would regularly, every 18 months or so, do that with 50 top executives and have them write down what would be different … And that was an example of farming for dissent … To disagree silently is disloyal.

- Reed Hastings, former CEO of Netflix.

I think it’s safe to say that there’s no need to farm for dissent in any workplace.

Dissent grows wild and falls to the ground, ripe, plump, and juicy in every office, cubicle, assembly line, and staff room.

It isn’t dissent that needs farming.

It’s good, smart, confident bosses.

Bad Workers Make Bad Bosses.

We respect good bosses because we’ve had bad bosses.

We know being good means the boss keeping their positional power gun holstered - choosing instead trust, patience, and other ‘soft’ virtues. We know that takes courage. We respect the good boss and feel grateful for her faith in us.

Which may explain why good bosses can appear weak to the bad worker.

The good worker knows and responds to the virtues of the good boss.

The bad worker exploits them.

Often the bad worker has never had a bad boss, so doesn’t appreciate and value the trust of the good boss. The bad worker cannot succeed on their merits, and therefore must exploit the ‘weakness’ of the good boss.

The bad worker’s exploitation of the good boss is why we respect the courage of the good boss.

The bad worker’s exploitation of the good boss is why we have much more bad positional power bosses.

And why bad workers make bad bosses.

What Do You Think?

‘Let’s go around the table and hear what everyone thinks is the issue and what we should do about it.’

When the boss opens a meeting with this line or something similar, you know it’s going to be a good use of everyone’s time.

Not so when the boss opens with ‘Here’s what I think. What do you think about what I think?’