Good Decisions Are Not Made in Meetings.

Step 1: Step Back. In a meeting, there is nowhere to step back. Meetings are the workplace equivalent of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. Performance spaces. Most often occupied by one person – the ‘leader’ – reciting a soliloquy. The rest of us sink back into our chairs - assuming we’re not at a Standup - (did Standups survive Covid?) behind our poker faces. There’s nowhere to wallow and scream ‘Why me?!’

Step 2: Define the Issue. It should be in the UN Convention on Human Rights that to call a meeting without defining the issue to attendees beforehand is a Crime Against Humanity. Forget Agendas. They’re overrated. Think about the Widget. What do we need to do to make our Widget? Begin the email with: ‘You are invited to meet to help me to decide whether…’. Sounds clunky? Yes. Three reasons: One, we don’t get invitations like that. Two: meeting convenors are uncomfortable about being open that they are decision makers because people in organisations are not used to being decision makers and to say as such sounds pompous. Three (and most importantly): Meetings are not held to make decisions. They are most often a power flex.

Step 3: Assess the Information. Information can be collected at meetings by the decision maker convenor. It can be assessed through discussion. Combining the two is not ideal. Information is being collected via the attendees and assessment has already begun in everyone’s minds. Usually Jack will say something and Jill will respond, often before Jack has finished. Or at the very least, Jill will be rehearsing her response in her mind, slowly disembowelling Jack’s speech while it’s still alive. Jack will often produce new information (otherwise, why is he here?) that may trigger a response in Jill where she needs to Step 1 – Step Back. She can’t. She needs to perform. She responds with her thinly veiled emotion. The rest of us are being entertained. Or bored.

Step 4: Check for Bias. Meetings could be like filtration plants where biases, conflicts of interest, prejudices and prejudgements are exposed and named and acknowledged and purged. People have to feel very safe in meetings for this to happen. As meetings are where we get to see each other stride along the catwalk while we size each other up, we’ve all got our best makeup on our serious faces and stomachs pulled in and we’re not going to show our blemishes. Finally, meetings are the breeding places of Groupthink.

Step 5: Give a Hearing. Meetings could be an opportunity for a person likely to be affected by a decision to be heard on why it shouldn’t be made. But this smacks of ganging up. ‘Hey, Fred! What are your thoughts on the office restructure that will result in you losing half your staff?’ Poor Fred just wants to Step Back and do a job search on LinkedIn. He’s in no fit state to contribute to his survival.

A meeting might be part of Step 2 or Step 3.

But only with an exceptional list of attendees should a decision be made in a meeting.

Sinner.

'If another lawyer checked your boss's work as closely as your boss checks yours, they'd find as many if not more mistakes.'

- Advice from a senior lawyer to articled clerks.

'I might be wrong.'

- Abbot Placid Spearritt at the beginning and end of every speech.

'Remember - we're all sinners.'

- Advice from the former Anglican Archbishop of Perth, Roger Herft

''Who is Jorge Mario Bergoglio?" "I am a sinner. This the most accurate definition. It is not a figure of speech, a literary genre. I am a sinner." '

- Pope Francis

Weakened by Power.

And so it was a fundamental change culturally. Because before that the aristocracy of JSOC had been measured by their machismo or their strength. And very quickly your value was largely determined by your willingness and ability to think through the problem. We had to become the smart guys.

A sign of intelligence is the ability to recognise the better argument than your own.

You can’t recognise the superior argument to yours, if you don’t know what your argument is. An argument requires two parties. Argument helps refine our position.

Positional power, if routinely deployed, removes the need to think. It thus weakens the ability to think, and thus to argue. Decisions are made based on positional power, which inevitably sows seeds of discontent, conflict, complaint, and open challenge.

Threats loom large and are defended with positional power. Internally and externally.

With every response from strength, we grow, (both individually and organisationally) intellectually and morally weaker. Requiring more positional power to be deployed to quell disquiet.

Inevitably, a threat materialises from a higher power. A better argument.

Collapse.

This is the story of empires. Of organisations. Of people.

Weakened by power.

Time.

I found a card sent to my deceased 93 year old aunt by her friend. My aunt spent her last year in care, after 25 years of living alone, retired at 60, having never married.

‘I hope you can read some of those books you haven’t had time for until now,’ her friend wrote.

You’ll have time during your lunch break.

You’ll have time after work.

You’ll have time on the weekend.

You’ll have time on the long weekend.

You’ll have time on your holidays.

Time when you retire.

Time.

As If.

The most enduring lies are those that are a notch shy of the truth.

The ‘As If’ lies.

They look as if they are the truth. They could be a lie, but it’s too awkward to challenge them, only to have the ‘How dare you!’ pearl clutch rebuke. It’s too time consuming and risky to look closely and interrogate the lie.

And thus we become complicit. We tell ourselves ‘It looks as if it’s the truth, so I’m going to tell myself a story that it is the truth to stop the dissonance in my brain. And to have an alibi if I’m wrong. I will say ‘It looked As If it was true’. I’ll close any gaps in information or logic by making assumptions so my story is coherent’

We create our very own ‘As If’ story. Except it’s not a lie now, because it’s ours. And we don’t lie

We accept the lie and it becomes our lie. And someone else sees us accepting the lie, and thinks ‘Well, if he believes it, then…’.

We thus own our As If lie, and feel the need to defend it, not only in our own minds, but if questioned about it. We stand defiant in the witness box alongside the liar.

The original As If lie, spawns new, unique As If lies. Particularly in a bureaucracy. The burueascrucy is expert at ‘As If’ lies because it has layers of detachment from the original As If lie, each bureaucrat able to justify why they acted in reliance on the As If lie above them. ‘It came from Head Office, so I had no reason to question it.’

Eventually some poor soul gets caught out in their As If lie that may be far removed from the original As If.

‘But I was only acting on another As If!’ they plead.

The organisation doesn’t care. It acts As If it’s found the bad apple and tosses it from the barrel, and moves on.

As If it’s fixed itself.

Poison.

The story goes that St Benedict reluctantly left his hermit life in response to the persistent pleas of a group of monks who begged him to be their Abbot.

They responded to his leadership by trying to poison him.

The expectation of a Saint is that he resisted, and persevered, and served, and suffered.

No. St Benedict left, and searched for somewhere to ‘employ himself more profitably’.

Often if we’ve been in a job too long, we lose perspective of our uniqueness. Over time, the organisation poisons our confidence and self-esteem.

It’s good to take our labour and talent and ideas elsewhere. To be reminded of their value in the eyes of another employer.

Cliff Hanger.

I had a school friend who would go to libraries, find the Agatha Christie novels, and rip out the last page.

‘It’s preparing people for real life,’ he explained.

The Noisy Silence.

Silence is often noisy.

The silence of meetings and emails and strategic plans and mission statements and vision statements and marketing and cliché and more meetings and position papers and presentations and reports and surveys and feedback and more meetings.

Organisations are designed, built, and operated for noisy silence. Bureaucracy and processes designed to put a truth in the mouths of people so far removed from the Truth that they can speak honestly about their truth.

Muting the Truth.

Muting our humanity crying out for someone to listen with the ear of the heart.

Drop the Digital.

I wonder when we’ll drop the ‘digital’.

And the ‘virtual’.

The ‘cyber’.

Even the ‘e’.

To anyone under 20, it’s just ‘information’ or ‘learning’.

Or Life.

Car Park.

The Architect Nonda Katsalidis engaged graphic designer Garry Emery to ‘do something interesting’ with the signage in the underground car park in Melbourne’s Eureka Tower. Garry decided to blend the functional information of signage - instructions of what to do - with entertainment.

He identified all the residents who used the car park needed was four words - In, Out, Up, and Down. He painted them in huge letters up the wall and across the flat ground below. To the stationary or first time viewer, the letters appear as abstractions; barely letters, let alone words, let alone instructions to the visitor.

It’s only when you are in motion when the distortions align with each other and snap into place as words. As you drive your car through the space, an abstract pattern forms the word ‘Up’, informing you about where your motion will take you.

As Garry describes it, the abstractions become legible ‘at critical decision making points.’

Once your movement reveals the words, you can’t not see and read them.

Our process of good decision making sets us in motion.

It moves us through our environment, revealing hidden cues.

Like Garry’s signage, what have been incoherent abstractions, indecipherable and random, form patterns that communicate, guide, and inform our decision making.

What are distortions to the static or pedestrian, become legible to the decision maker.

What is meaningless forms patterns giving our journey both direction and meaning.

The Moment.

The Iroquois helicopter skids caressed the earth then settled amid the swirling dust.

The crewman signalled for us to jump out of both doors and run bent over beneath the throbbing blades to the ten o’clock and two o’clock positions like we’d practised back at the Base. The Iroquois lifted off and smacked us with its downdraft as it swept overhead and away.

I scanned the area. Nudged the cadet next to me. ‘This isn’t our rendezvous point.’ He nodded. ‘I reckon they’ve deliberately dropped us off at the wrong location,’ he said. We’d spent hours planning our mission legs on our maps. For nothing.

The Directing Staff crawled along the ground to where I sat, tightening my hat and checking my webbing.

‘You’re Section Commander for the first leg,’ he said. ‘Over to you.’

I looked down the line of faces looking back at me.

I waited for someone else to do something.

Nobody was going to. Because I was the Someone.

I was in charge.

Nothing would happen. Nobody would move. We would stay here until I said otherwise.

My stomach clenched.

Still nobody moved. The Directing Staff had crawled back to end of the loose line of cadets lying in the dirt, waiting to observe and assess what I did next. Waiting for me to do something. To literally lead.

I wonder if every person who’s talked about, or taught, or claimed, ‘Leadership’ can identify the moment when they felt - not theorised about - what it feels to Lead.

I wiped the dust off my watch.

It was 11am on Saturday January 24, 1981.

There are Things I Don't Know.

There’s a story that the barrister and author Stuart Littlemore KC was found at his desk with a dictionary open. The interruptor sacrastically said ‘You mean to say there’s a word you don’t know, Stuart?’ To which Mr Littlemore closed the dictionary and said ‘Not any more.’

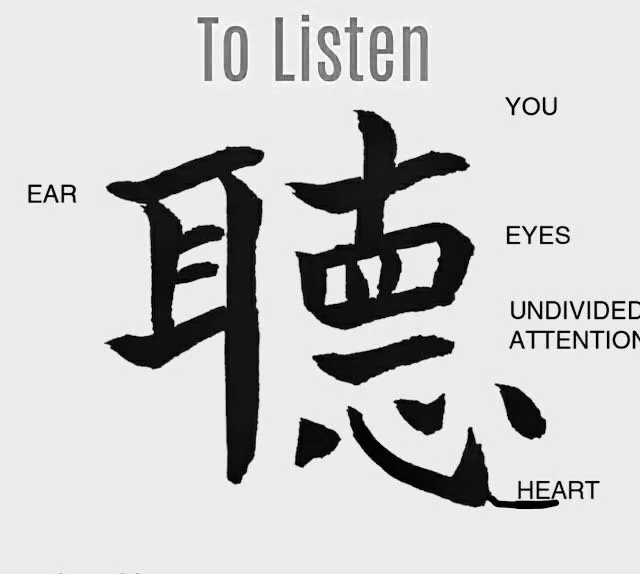

Listening is an expression of self-doubt.

It is a practical response to the truth of ‘I have an opinion, and it might be wrong.’ Taking the time - five seconds or five days - to listen. To be the naive inquirer. To humbly pray before the altar of ‘There Are Things I Do Not Know’.

Step Three of the Five Steps to Good Decision Making is Assess the Information.

You’ve done Step One - Step Back and thus purged yourself of the beat-myself-up form of self-doubt. Listening is an outward focussed, eager, almost excited act of humility and service.

As the Benedictines say: Listen with the ear of the heart.

Barley in the Wheat

‘Unfortunately there’s some barley in the wheat crop this year,’ the new farm manager reported at the monthly farm meeting. ‘It was probably introduced when the last farm manager did the seeding.’

Barley in the wheat.

Easy to blame the last person for the barley in the wheat. The inherited problems. They’re not here to defend themselves. To challenge you. You escape responsibility. You look like the victim. It’s not your fault. You’re off the hook. Unblemished record. Nothing to learn from this other than the other bloke was not as diligent as you are. You get instant status as Better Than The Last Person.

Finding fault in the last person, and changing what they did with a tut-tut, is a common way of stamping your authority and status in your organisation. It’s probably the easiest work you’ll do during that honeymoon period.

Except that by blaming the last person … you’ve blemished your character.

People are wary of those who blame others. Because they are an ‘other’ who might also be blamed.

By blaming the last person, you’ve sown seeds of doubt in your own field, that will grow, and one day will be harvested, and feed you and those around you.

Barley in the wheat.

Spend the Time.

Everyone every day gets 24 hours. That's all. And when we spend time on other people doing things that apparently are inefficient, we are doing something very important that is actually efficient. We are spending time - something that is precious that we can't get more of - to demonstrate to the other person that we see them, and that we value them.

- Seth Godin

We honour a person who may be adversely affected by our decision when we spend our time on the Five Steps to a Good Decision . We honour them with our most precious resource.

60th Anniversary.

We subject all facts to a prefabricated set of interpretations. We enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought. Mythology distracts us everywhere.

- President John F. Kennedy

On the 60th anniversary of his death, the words and actions of President Kennedy continue to guide us in the theory and practice of good decision making.