The Long Story

I was leading a conversation with some senior executives on a leadership forum recently when one of them asked me: 'Who is the leader who has taught you the most?'

I'd never been asked that in the then 35 years of studying and attempting to apply good leadership in military, business, government, religious and education organisations.

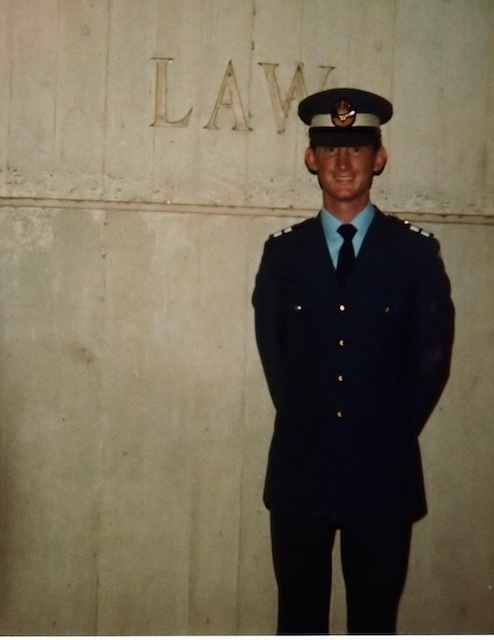

'Leadership' is a quality that is sought after and talked about in all organisations. I was a Legal Officer in the Royal Australian Air Force for 12 years and a cadet for 10 years before that. I have served in the Specialist Reserve for another 24. The Defence Force is one of few employers who expects Leadership to be a core competency. It is therefore continuously taught, applied and assessed in the workplace.

The style of leadership exercised in the military relies heavily on the formal rank and command hierarchy and is therefore not always useful outside of this disciplined environment. Yet the cadets and RAAF taught me the theory and appointed me to positions where I was expected to apply it.

I worked for and alongside some outstanding officers and junior and senior non-commissioned officers who taught me through their words and actions about what good work looks like and what it takes to do it consistently. From Corporal Julie McKenzie in my first posting to Warrant Officer Col Greef, RAN in my last and Warrant Officer Tanya Fraser seemingly in between, I have worked with 'subordinates' whose professionalism and patience taught me that good leaders are made by good 'followers'. They generously allowed me to learn what it feels like to lead successfully.

(One of my many theories is that it's harder to do good work if you don't know what it looks like. My friend Ian called this the Deperdussin Theory - named after one of the first aircraft that the RAAF flew in 1912. His view was that if a Deperdussin flew over a lost tribe in the jungle, they would think that it was the most incredible machine and worship it. But only because they'd never seen an F-35.)

I was privileged to work for senior officers for most of my career and as a relatively junior officer and lawyer. My first posting after Officers Training School was as a legal adviser to the Commander of about a third of the people and aircraft in the Air Force. My second was to the Air Officer Commanding Western Australia. My postings after that included advising the Commandant of the Defence Force Academy, the Chief of Air Force and the Chief of the Defence Force, with some work for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Department of The Prime Minister and Cabinet along the way. In each case I watched how experienced leaders used their advisers, thought through and executed on their decisions and then managed and learned from the consequences and incorporated it into their next decision.

The military environment in which I practised Law also demanded that I developed specific skills in the manner in which I provided legal advice. The commanders and other senior officers who I mainly advised demanded clear, practical and accurate verbal or written legal advice in a relatively short time after asking for it. It would be incorporated into a decision that was soon executed, allowing me to see the consequences and therefore learn from them.

The seniority of most of the officers that I advised also demanded that I be confident in my advice and stand by it if it was contrary to what they expected. I was very fortunate to have had commanders early in my career who were prepared to argue with me, yet be persuaded by reason and adopt the advice, and even in some cases to stand by it when their decisions were challenged by their own superiors. I owe a great deal to those wise women and men for the confidence and resilience that their leadership and trust nurtured in me.

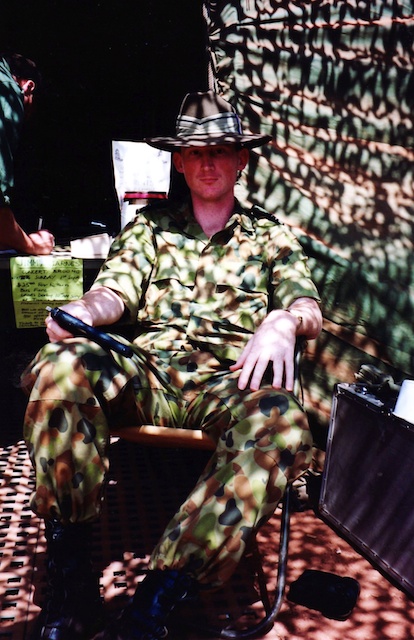

If you're laughing at this photo it means you've been an airman in the RAAF.

As a teenage cadet before I joined the Air Force I learned from the senior cadets who seemed so confident and proficient in the way that they got things done through the cadets under their authority. Some of those teenage role models became my friends and continue to teach me today. We got to apply theories of leadership as senior cadets each week. Ian was the first person to show me the power of using written sources of authority to respectfully question 'the way that things are done', to have the courage and self-belief to take control when challenged by superiors to prove his ideas, and to use both qualities to deliver independently assessed measurable results through leading in a competitive environment. All at age 15. I have forgotten and 're-learned' several times what Ian taught me by his example thirty five plus years ago. What Ian taught me through his sheer will, Shaun polished into Officer Qualities. A perfect combination of mentors for a teenager.

The Officer Commanding RAAF Base Pearce Air Commodore Ashworth, Ian, and me as we appeared on pg 3 of The West Australian the day after we both Duxed our respective cadet promotion courses as 15 and 16 year olds respectively.

Ian's example prepared me to battle the RAAF for several years to convince it to add Legal Officers into its Undergraduate Scheme. Prior to that, the military only accepted University students studying Medicine, Engineering and Dentistry to apply to finish their studies under Air Force sponsorship and to go on to serve as specialist officers in their professions. Why not Lawyers, I asked RAAF Recruiting for several years. Finally, in my third year of Law at the University of Western Australia, they appointed me as an Officer Cadet Legal Undergraduate. Possibly the first.

I was so fortunate to have Flight Lieutenant (now Wing Commander) Des Mitting as my first Administrative Officer. (Indeed, his leadership and professionalism made such an impression on me that until recently I had remembered him as my first CO.) At our first meeting, he was efficient, approachable and practical. He told me that my primary duty was to graduate from Law School and to complete my Articles and qualify as a Legal Officer. He told me that his job was to support me, and to leave me alone to study, as that was my duty at this stage of my Air Force career. Great leadership. Widget Thinking. He then introduced me to the most important person in any RAAF unit, the Corporal in charge of the Orderly Room. She showed me how to get all my allowances and pay and made sure that I got everything that I was entitled to. The CO, Wing Commander Mitting and their small team made sure that I had nothing to worry about other than to pass my exams. They were at the end of the telephone when I needed them and otherwise they got out of my way. I think I took all that for granted as normal.

The only significant 'duty' that I had to undertake during my studies was during one University break. I 'volunteered' to participate in a three day anti-terrorist exercise in which I was a 'hostage' who was 'rescued' by members of the Special Air Service Regiment (SASR). We were ordered afterwards never to disclose any of the weapons or tactics that we witnessed - which doesn't matter because it was two and nine-tenths days of boredom - and ten minutes of blurred action as we were 'liberated'. The speed, precision and creativity in which those soldiers perfectly achieved their mission gave me first hand evidence to support all that I'd heard and read about the skill of the SASR. I encountered special forces soldiers a few times during my career and I was always struck by their low-key demeanour and - ordinariness. It was a vehicle containing SASR soldiers who stopped to give me a lift to Headquarters when every other vehicle had driven past during one hot day on exercise. On another exercise I was viewing a video of an F-111 bombing mission to respond to some international law issue when I heard a voice from behind me say 'Excuse me - may we sit in?' I turned to see three bearded and filthy SASR soldiers who had returned from two weeks on patrol. I learned from those brief experiences with these élite soldiers that they simply did their very dangerous jobs very well and let everything else take care of itself. Widget Thinking.

GPCAPT (Ret) Garry Lawton was the Reserve Panel Leader and therefore my first RAAF Legal boss. He was also my Principal as an Articled Clerk. Garry told me that there are two things that make a good lawyer: the ability to build good relationships with other people and the ability to write a good letter. 40 years later I know that Garry was right and I'm still benefitting from that simple lesson. As my Principal during my Articles year, Garry threw me into the deep end of the legal pool and assumed that I could swim personal best times. My first appearance was in the Supreme Court and although a mere Articled Clerk Garry left me to brief Queens Counsel in their chambers and sit beside him in Full Court hearings. I failed many times and let Garry down and he made sure I knew when I had fallen short of what he expected of me. It was a tough year and Garry made sure that I was as ready as I could be when I was finally admitted to practise as a Barrister, Solicitor and Proctor of the Supreme Court of Western Australia.

Flight Lieutenant (now Air Commodore) Kathy Dunn, Directing Staff of Charlie Syndicate, 1/90 Officer Training School.

Flight Lieutenant Kathy Waugh (now Air Commodore Kathy Dunn AM) was my Directing Staff (or 'DS') during Officer Training School (OTS). Kathy was the epitome of work hard - play hard. Her personal example of professionalism and enthusiasm overcome the mediocrity in leadership theory and example that was otherwise my disappointing experience of OTS. Kathy was a powerful positive influence on my attitude towards women in the military at a time when the Defence Force wasn't as accepting as it is today.

My first posting after graduation from OTS allowed me to learn from five different yet effective leaders in the formative eighteen months of my first posting as a Legal Officer.

Squadron Leader Steve Watkinson was my Legal boss. Steve and I had our moments - and he was an excellent lawyer who allowed me to learn the technical craft of military lawyering in the days when there were no Initial courses for new legal officers.

When Steve was attached away for a few months, Squadron Leader Allistar Twigg, a former RAAF Canberra Bomber, Neptune and Orion Navigator turned Barrister and Reservist Lawyer took me under his wing (pun intended). Allistar blended a thorough and practical legal mind with a relaxed attitude and a genuine concern for the dignity of others, regardless of rank or status. Allistar's approach to professional life meant more to me because I knew that he had been-there-and-done-that - both in the 'sharp end' operational flying world of the military, as well as the real world of the civilian Bar as a barrister. He was the first example of what I have found so often in professional life - those who really know their stuff are least likely to need to broadcast the fact. Allistar showed me that being very good at your job didn't mean that you had to take yourself or others too seriously, and that as long as the work was done then you could play a lot as well. I devoured everything that he taught me both in the office and over long lunches in the Mess. I owe a lot of my philosophy around the law of armed conflict to my conversations with Allistar over a light lunch in the Point Cook Officers Mess Ante Room as the First Gulf War approached and was fought.

Squadron Leader Allistar Twigg, Navigator, Barrister, Legal Officer. Always let his excellent legal work speak for itself and never took himself too seriously.

Group Captain Ron Gretton was my first CO 'client' on my first posting after OTS. He had joined the RAAF as an apprentice and had risen through the ranks so he had learned everything he knew by doing. From our first meeting Group Captain Gretton was warm and smiling and generous with his time and patient with my inexperience. I always got the feeling that he assumed that I knew everything about the Law despite being so junior and he never once treated me like the novice lawyer and officer that I was. In the years that followed I was patronised and ruled over by lesser ranked superiors who did not have Group Captain Gretton's wisdom, humility and comfort in his own skin.

Air Commodore Ken Blakers was the Air Officer Commanding Training Command and therefore my primary 'client'. He had hundreds under his command at Headquarters yet he always remembered my name. One day early in my posting he saw me waiting at the Orderly Room counter and asked if I'd like to join him on a staff visit to one of the Bases under his command. I spent several days with him in meetings with commanders and other senior officers on the Base and watched how he listened, carefully framed his questions and spoke clearly and plainly to his commanders. It was a precious and powerful experience to be able to observe how one of the most senior officers in the RAAF solved problems and exercised command with intelligence and respect for others. After each meeting he would ask me 'What did you think of that, Bernard?' and the listen intently as I offered my opinion. He spoke respectfully yet openly of the strengths and weaknesses of the behaviour of some of the officers. I felt privileged to be trusted by him and to be given a real life command tutorial so early in my career as an Officer. Yet again I had been fortunate to be commanded by an Officer who was experienced, wise, self-assured and eager to teach me. I was beginning to assume that this was the norm with all officers. I was head over heels in love with my job.

Flight Lieutenant Helen Crozier was the Base Legal Officer (BLO) at RAAF Williams where HQ Training Command was located. She had taught our OTS Course Military Law and all the men on course fell in love with her while the women appeared to envy her poise and cool professionalism. Helen was an excellent instructor and a very good presenter and I felt proud to be a Legal Officer when she was around. After I graduated, Helen shared with me the challenges of being a BLO and we eventually shared a house in Melbourne. She never realised what a good lawyer that she was and agonised over some of the advice that she had to give that she knew would not please her commanders. While I had Allistar as a role model for giving legal advice without fear or favour, I had Helen as an example of how much courage it often took to do so.

Wing Commander John Oliver, Administrative Staff Officer, RAAF Base Pearce.

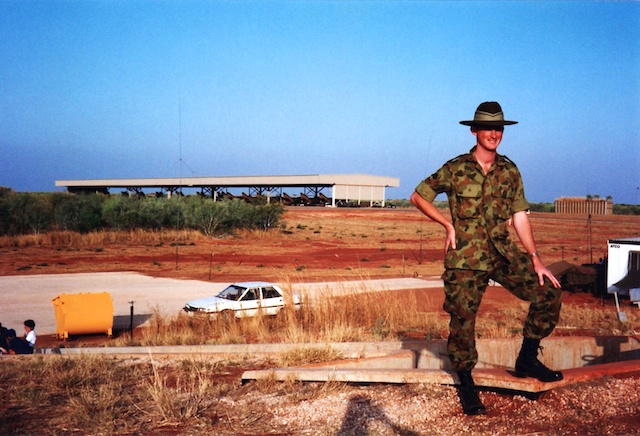

After two years of excellent theoretical and practical teachers in Law, leadership and decision making, I was ready for my first solo posting as the inaugural Base Legal Officer of RAAF Base Pearce in Western Australia. Once again I found myself working for and with three excellent leaders.

My immediate boss was Wing Commander John Oliver. He was approachable, friendly, efficient and despite outranking me, never talked down to me like so many officers do to our subordinates. He assumed that I was good at my job and expected me to give good advice on the wide range of legal issues that a Base Legal Officer is asked to advise upon. He appointed me as Officer in Charge of the Airmens Club so that I could gain experience in managing people. I worked with the airmen on the Base to help them to run their social club. They were all very respectful, and I knew that this didn't mean that they respected me. I knew better than many officers to never confuse the military courtesies that airmen are obliged to extend with any measure of how good an officer was at their job.

RAAF Base Pearce Warrant Officer Disciplinary Henry Adam.

I worked with the Senior Airman on Base, the Warrant Officer Disciplinary (WOD) Henry Adam. He took the credit for establishing the Base Legal Officer position at Pearce before I was appointed to it, and I engaged with him almost every day of the nearly two years that he and I served there together. He never failed to call me 'Sir' but I knew who was really in charge. Henry was brilliant at his job of maintaining discipline on the Base on behalf of the Officer Commanding. We worked together from matters ranging from interpreting military legislation to my role as Ceremonial Officer in charge of guards of honour and other parade ground duties. Ultimately the role of the WOD required Henry to walk the talk. His dress, bearing and behaviour had to be exemplary if he was to demand the same of the officers and airmen on Base. I never felt more motivated to be a better officer than when I was working with Henry. My two years with Warrant Officer Henry Adam and the faith that he showed in me have been one of my greatest privileges in my time in the military.

The Air Officer Commanding Western Australia and my ultimate boss at RAAF Pearce was Air Commodore (AIRCDRE) (subsequently Air Vice Marshal) Neil Smith, AM MBE. His qualifications as an Engineer and Fighter Pilot meant that he was both a thinker and a doer. AIRCDRE Smith had been in the RAAF for 30 years and I had been on full time duty for only two. He was four ranks senior to me and probably thirty years older. Yet as with all the best officers that I met, he did not rest on any of these advantages to 'manage' me. He would listen to me advance a legal argument, challenge my logic with lots of robust questions, and then make a decision. AIRCDRE Smith was the only officer that I knew to have been brave enough to apply the principle of providing 'top cover' to subordinates. He relied on some advice that I gave him to make a decision and was subsequently publicly criticised for it by his boss - a two star Air Vice Marshall - at a conference in front of other base commanders. I learned from another source that he had responded to the AVM that he could still find no fault in my legal advice and therefore stood by his decision. AIRCDRE Smith also defended me against a Navy Commodore who complained bitterly to him about some advice that I had given to a Naval officer. His confidence in me and willingness to act on it even when challenged by superiors inspired genuine loyalty and respect from me and led me to work even harder to make sure that I gave him accurate legal counsel.

Group Captain Brent Espeland briefs Orange Force Sea, Air and Land Commanders and other members of Headquarters on Exercise Kangaroo 92.

I am very fortunate to have never had to serve in conflict. The closest experience was a million miles away from that level of danger - on three exercises. On Exercise Kangaroo I was legal adviser to the 'enemy' Orange Force Commander, the late Group Captain Brent Espeland (subsequently Air Vice Marshal Espeland, AM). I gave him daily advice for six weeks on the law of armed conflict in the relative comfort of an underground bunker. His calm, even energy never wained as he coordinated his sea, land and air forces without a break. I watched my advice to him take form in some of the decisions he made in the deployment of his assets and the conduct of battles. He involved me in all of his briefings and encouraged all of his commanders to seek my advice in their decision making. GPCAPT Espeland was approachable, good-humoured and never relied on his seniority to get things done. I saw how his confidence in me encouraged the other 'operators' to believe that a lawyer may have some value to add to their military decision making. Midway through the exercise a Colonel from Sydney flew in to meet with me to find out how the Orange Force Commander was so effectively integrating legal advice into his conduct of the 'war'. I had been on exercise before and been a mere token presence despite offering the same service to the commander. It was GPCAPT Espeland's leadership that allowed my advice to be heard and amplified. At the 'hot washup' debrief he announced in front of the Headquarters staff that before the exercise, law of armed conflict had not even been on the list of command capabilities that was to be assessed, and that at the end, it was the top priority. It was his leadership that had created the opportunity for it to be so.

Almost all of my role models for military leadership were in the first five years of my Permanent and Reserve career in the RAAF. In the 36 years since then, there have only been a handful who have stood out.

I was posted from RAAF Base Pearce to various postings in Canberra until I transferred from the Permanent to the Reserve five years later. Group Captain Alan Hemmingway was a legal officer who held various roles in my legal chain of command in that time - and until recently continued to do so as a Reservist. GPCAPT Hemmingway's greatest example is a rare eagerness to openly admit - almost boast - that he relies on 'better legal minds' than his when preparing advice for the various Chiefs of Air Force that he has served. He was another example of someone senior to me both in rank and expertise who demanded that I rise to his expectations in a very real and compelling way. GPCAPT Hemmingway didn't need to manufacture artificial opportunities to 'coach' or 'mentor' me or to give 'feedback'. Many times he grabbed my service cap from its hatstand and tossed it at me and said 'Come with me - I need a real lawyer' before taking me to some one or two starred officer to give legal advice. He thrust me into situations that were almost out of my depth and I never had time to realise this. I enjoyed his dry and sharp wit almost as much as I admire his lucid writing that stands out from the predominantly clumsy over-written expression of most senior officers who appear to think that their rank speaks in turgid language. GPCAPT Hemmingway continues to teach me that there is no shame in a leader saying 'I don't know - but this subordinate will' - and that leaders shouldn't take themselves too seriously. I can't think of him without smiling.

Commodore (subsequently Rear Admiral) Brian Adams, AO, RAN was the Commandant of the Australian Defence Force Academy (ADFA) when I was the Director of the Military Law Centre which was not part of ADFA but a 'lodger unit' there. He had his own Academy Legal Officer and sought my advice either when his lawyer was conflicted out, or when he or his legal officer wanted another opinion. Commodore Adams had joined the Navy as a Junior Recruit and risen through the ranks. He was appointed to command ADFA during one of its many 'transitional' times and was the right man for the job. He dealt with issues ranging from sexual assault to change management. He was modest, fair, unafraid to confront evidence of shortcomings or to seek advice on what to do about them, and to act decisively and support his subordinates in the execution of his decisions. My meetings with Commodore Adams left a powerful impression on me. I would sit in one of the armchairs in his office and listen to him clearly present the facts of a situation, describe his assessment of them, state the outcome that he wanted, and then sit back and listen to advice as to how he could do it. As with all the leaders I admire, he expected the best of me and did not seek to use his rank or status to influence my advice. He relied on evidence and an clear understanding of what he had to do to make his decisions.

Flight Lieutenant Michael Kar, Base Legal Officer RAAF Base Amberley. The bravest Legal Officer and lawyer I knew. His integrity and determination to give fearless legal advice were rare among officers who depended on their superiors for good postings and promotions - both of which were largely denied Michael.

My friend Michael was the most courageous Legal Officer in the Defence Force. With the exception of Commodore Adams, he did not have the quality of commanders that I had. They did not acknowledge or appreciate his lucid, practical, fearless advice. Michael suffered the consequences in terms of slow promotion and poor postings. Yet he continued to offer advice without fear or favour. The Defence Academy could not have implemented the reforms and cultural change if Commodore Adams had not had Michael as his legal adviser. Far lesser officers received honours and awards for just going through the motions. Michael taught me that true leadership demands quiet sacrifice and its only certainty of reward is the satisfaction of being done.

I resigned from the Permanent Air Force with the rank of Squadron Leader (equivalent to a Major in the Army) and have been a member of the RAAF Specialist Reserve for the 24 years since.

One of the unique benefits of being appointed as an Officer in the Defence Force is that without having to do anything to prove that I could lead, I acquired ready-made 'followers' in the form of everyone junior in rank to me. The discipline and professionalism of the soldiers, sailors and airmen means that they at least pretend to defer to my seniority. They have patiently endured the consequences of my relative inexperience and have always tactfully offered their guidance to me. Every member of the military who has ever found themselves under my authority in any way continues to teach me about the obligations and privilege of leadership.

Warrant Officer Tanya Fraser, CSM, representative of the many Senior Non-Commissioned Officers, Airmen, Soldiers and Sailors whose professionalism, wisdom and patience allowed me to learn so much about the obligations and privilege of leadership.

I went from the relative predictability of the Permanent Air Force, to the chaos of senior management of an information technology security start up company. I spent the next three years in the world of corporate law, human resources, industrial relations and almost everything in between as one does when helping to grow a business from eight people to 160. Allistar Twigg was there for much of that time and helped to make the shift from the security of the Defence Force to the week-by-week existence of a start up.

I found my way back to Perth where I was invited by the Abbot of the Benedictine Monastery of New Norcia to be the Town Manager. My immediate boss was a monk - Dom Chris Power - the Procurator (business manager) of the town. Dom Chris's ability to write well affirmed the advice given to me by Garry Lawton in my Articled Clerk days. Even before I began work at New Norcia, I read many articles written by Dom Chris in various newsletters, journals and other material published by the monks. His prose was clear, precise, and in a style that reflected one of the maxims of St Benedict: 'In all things may God be glorified'. Words matter, and Dom Chris knew this.

Dom Christopher Power, monk of New Norcia and the best user of written language that I've encountered in my work.

Father Placid Spearritt was the Abbot of New Norcia and therefore my ultimate boss. Father Abbot was fluent in multiple languages, including Hebrew and Latin, and was wise and intelligent. Yet he would respond to most crises with a shrug of the shoulders, a gentle smile and often nothing more than 'That's okay.' If I ever sought his counsel about some leadership decision I was facing, he would usually answer with a half chuckle and 'Just be yourself, Bernard'. It was enormously unsatisfying each time that this was the sum total of his wisdom. And yet Placid was right. It is nearly twenty years since he first gave me that advice, and every time I reflect on it I am reminded that it was the best counsel that I ever received. What's more, I think that every person who has influenced me has said in their own way - 'Be yourself'.

The Most Reverend Roger Herft AM, former Archbishop of the Anglican Diocese of Perth and Metropolitan of the Province of Western Australia

At our first meeting after he appointed me Director of Professional Standards for the Anglican Church in Western Australia, Archbishop Roger Herft, AM leaned forward with his gentle smile and said 'I think that it's important for you to remember as you do this work that we are all sinners.' That simple advice, reinforced by Archbishop Roger's actions in support of my work as Director in preventing, detecting and reporting child sexual abuse, has remained with me. The word 'sinner' isn't even fashionable in religious circles and has no currency in the secular workplace. Substitute 'imperfect' perhaps. Archbishop Roger's words and deeds complemented those of Abbot Placid remind me that our brokenness may be all that we have in common.

Father Placid Spearritt, Sixth Abbot of New Norcia

I have been extremely fortunate to have had so many excellent leaders and mentors, particularly in the early years of my career. And yet I believe with great sincerity and genuine gratitude - that I owe much of what I know about leadership to the bad bosses and managers that I have worked for or with. The few unhappy workplaces that I have experienced forced me to deeply examine what it was that made them that way and what I could do to fix them. Probably like everybody, I have watched in disbelief as mediocre people with little talent and often less integrity have made their way to high office. Some of these ascensions I've reluctantly understood. The explanation for the success of others still escapes me. Perhaps - as my friend Rick once said - it's simply because 'some people are just stupid'. I probably owe some of my good fortune to that same 'stupidity' in a couple of my bosses.

I also know very well that I was one of those bad bosses to some people I worked with - who wondered what I had to offer to the job - and worse - who I made feel unhappy.

I remembered each of those people's faces in the few seconds that I pondered the Executive's question: 'Who is the leader who has inspired you the most?'

From nowhere came my answer:

'My Dad.'